In this blog, we focus on “Eczema and the skin” unraveling the complexities that shape this symbiotic relationship. From birth canal colonization to the dance between Staph epidermidis and Staph aureus, we’ll navigate the key players influencing eczema and glimpse into holistic care through the transformative journey of a patient named Tyler.

Medicine can be terribly humbling at times, particularly when treating children’s eczema. But I have found that often my most humbling patient experiences are also where I learn the most about managing this frustrating disease. I want to tell you Tyler’s story as it provides a wonderful picture of how both the skin and gut play a role in eczema.

Tyler first came to see me as a gangly 8 year old who suffered from eczema for years. Her parents, Mark and Stacy, had tried all the standard traditional treatments including topical creams and steroids, eliminating dairy, oral steroids, antihistamines, and more. I was confident Tyler still had a sick gut, and so my first order of business was to heal her gut. After about 4 months of dietary changes, lifestyle adjustments, stress management and a supplement and probiotic regimen to resolve her deficiencies, she still had red, inflamed patches of itchy skin – minimal improvement. Many of her eczema lesions had become intermittently infected, with pus on top of the redness.

Mark and Stacy became highly concerned over the infected lesions, and couldn’t understand why our management thus far hadn’t seemed to help. Stacy brought Tyler to the office urgently one day to show me the worsening areas. “It just keeps getting worse and worse,” Stacy exclaimed. Tyler just sat there quietly trying not to itch her elbows. As I examined Tyler’s arms, she had large red areas of weeping eczema, with pus and drainage from multiple areas. It looked horrible.

Have you ever been in a situation where you did everything “by the book” but still were not getting the result you wanted? Did you double down on what you were already doing to see if trying harder would work? Then I remembered Albert Einstein’s definition of insanity – doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. I clearly needed to try something different with Tyler, but I wasn’t sure which direction to head.

New Directions

As I pondered Tyler’s weeping skin, it reminded me of several high school football players I had seen who had developed MRSA infections in the locker room. But Tyler had never been on a sport’s team nor had she been exposed to known MRSA infections at school. I began to research skin infections with eczema and it opened my eyes to a whole new aspect of eczema – the skin microbiome.

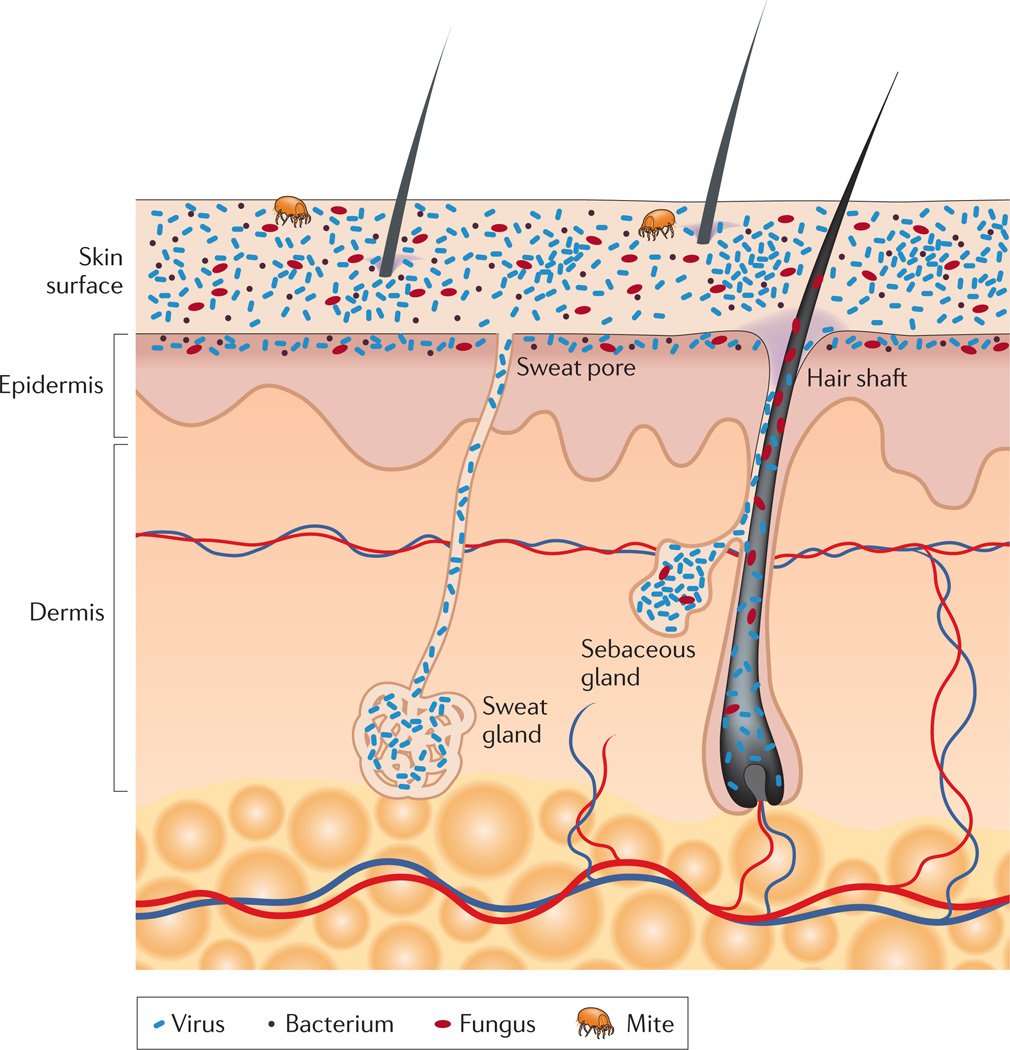

Our skin is the largest organ in our body and if you count all the dips, holes, and crevices for hair follicles and sweat glands, it actually has a surface area over 25m2 (about the size of a 2 car garage). And all that skin surface is covered in bacteria, viruses, fungi, and mites – YIKES. The skin provides a vital physical barrier, protecting our bodies from potential assault by foreign organisms or toxic substances. But it is also an interface for our immune system to interact with bacteria which may actually help provide an important function (just like in our guts). For example, many of these skin bacteria interact with our white blood cells, teaching them which bacteria to tolerate and which to attack.

While we are in the womb our skin is sterile and only becomes colonized as we pass through the birth canal. This presents another reason why vaginal birth is so important – not only is our gut microbiome established in the vaginal canal, but our skin is too. The skin microbiome then develops over the first year of life but is constantly changing based on changes inside our body, on our skin, and in our environment. However, our skin is rapidly changing at the same time. Skin cells are replenished every 14 days in a baby, and every 28 days in an adult. So microorganisms and our skin are engaged in a continual tango of acceptance or denial based on the microorganism in question.

The organisms on our skin are also very picky in where they choose their home. The living environment in our armpits is very different than on our knees (just smell any teenage boy) and specific bacteria capitalize on these differences. Lots of little holes and folds in our skin (termed invaginations and appendages), including sweat glands (eccrine and apocrine), sebaceous glands and hair follicles, are associated with their own unique microorganisms as well.

The characteristic smell of sweat is created when apocrine sweat glands, located in the armpits and groin regions, interact with bacteria in those areas and the resulting waste products have a sulfur-like odor. Similar types of bacterial/skin interactions are occurring continuously all over our bodies in an attempt to maintain a steady-state. And just like in our guts, some of the biggest balancing acts are between beneficial and problematic bacteria.

Meet Staph

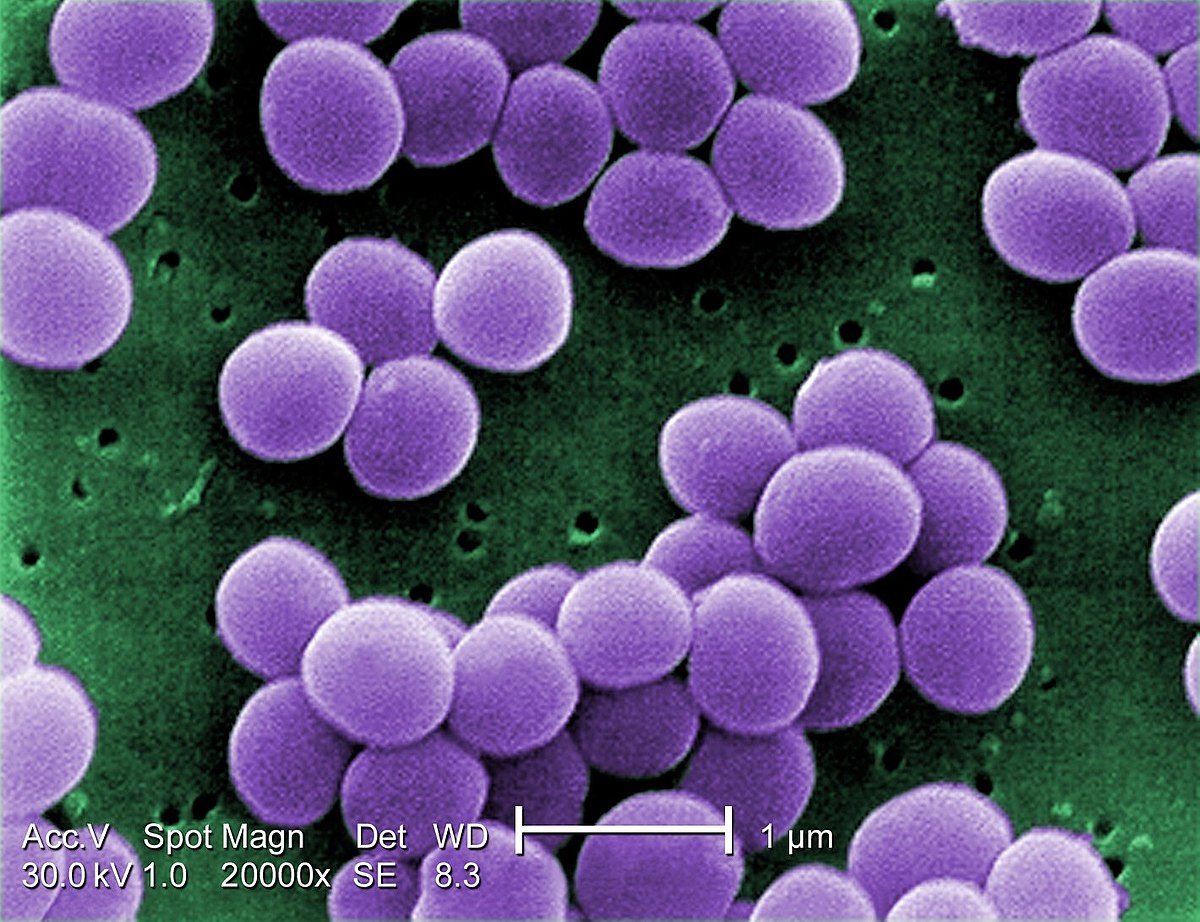

You have probably heard of a staph infection at some point. More than 45 species of staphylococcus have been discovered, with more likely to come. 2 specific staphylococcus species wage continuous war on our skin for control of the territory – staph aureus and staph epidermidis.

Staph epidermidis is the typically “friendly” bacteria on our skin that helps train our white blood cells. Cells in our skin (called keratinocytes) continuously sample the bacteria on our skin to determine if they are dangerous – and if they are deemed harmful, the skin cells initiate an inflammatory response and produce proteins that can kill the bacteria. And the skin is amazingly good at figuring out which bacteria to keep and which to attack – although we don’t understand completely why. But evidence exists, that staph epidermidis is a major player in helping the skin perform the evaluation process. Staph epidermidis not only directly blocks the growth of staph aureus and other dangerous species, but it also aids the proteins our skin cells make to kill the bad staph. Lastly, staph epidermidis actually can help calm down our skin immune response when it becomes too active.

Staph aureus plays the villain in this skin battle and clearly has a role in eczema lesions. More than 90% of eczema patients are colonized with staph aureus on both affected and non-affected skin, compared with <5% of healthy individuals. Add that to the fact that eczema patients have lower levels of those bacteria fighting proteins produced by our skin cells, and staph aureus quickly has an advantage. Another problem with staph aureus is that it secretes an enzyme to break down ceramide.

Ceramides are lipids (a type of fat molecule) that are found naturally in our skin; they’re the body’s built-in moisturizer. They make up the majority of the stratum corneum—the top layer of your skin—and are responsible for holding the cells together. In addition to acting as the glue that keeps the skin barrier intact, ceramides are moisturizing agents that make skin feel soft. Of note, ceramides make up much of the white cheese-like substance found coating the skin of newborn infants. By breaking down ceramide, staph aureus can disrupt the protective skin barrier, allowing it to enter our body. The breakdown of ceramide also leads to loss of moisture and subsequent changes in pH – and it turns out pH is pretty important in skin.

Understanding pH

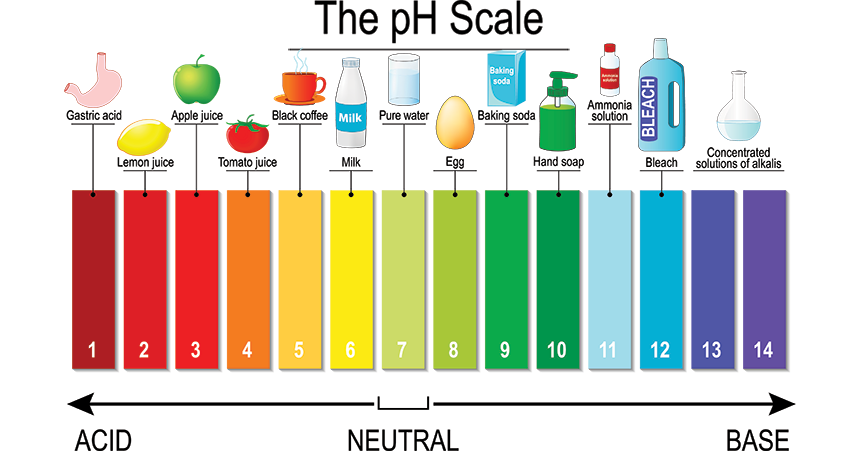

Back to a little basic chemistry here – pH determines if something is more acidic (pH below 7) or basic (pH above 7). Water is neutral with a pH of 7. Newborn skin begins with a neutral pH, and the transition to acidity begins in the first year of life, with greatest changes occuring in the first 2 months of life . Of note, pH changes go from more acidic to more basic in the elderly, in part due to ceramide deficiency that occurs with aging.

Although ceramide is important for maintaining acidic skin pH, it’s counterpart called Filaggrin is probably even more critical. You may remember Filaggrin from the eczema and genetics blog post, as a defect in the filaggrin gene is known to increase risk of eczema. In addition to providing strength to the skin barrier and holding in moisture, filaggrin causes release of amino acids causing the skin to become more acidic. And guess who hates growing in an acidic environment? Yep – staph aureus. The skin’s antimicrobial properties are optimal at acidic pH = pH 4-5, and many of the harmful bacteria on our skin can’t tolerate that low pH. Many other factors can affect pH though.

Body site plays a role in skin pH, with infants experiencing higher pH on extensor surfaces and prominences, such as the cheeks and buttocks. Children continue having higher pH on extensor surfaces such as inner elbows, wrists, ankles and behind the knees. Later in normal adult skin, the intertriginous zones (between fingers and toes) tend to have the highest pH.

A lot of things can disrupt our skin’s natural pH and break down the acid mantle. Factors such as what kind of products we put on our skin, the kinds of foods we eat, soaps, and other topical products, sun and UV exposure, smoking and drinking, and many others can disrupt the way the skin protects itself. Our diet in particular plays an important role in determining our internal pH and the pH levels of our skin. The acidic pH is critical to the overall function of the skin. . Staphylococcus and other pathogenic bacteria love neutral pH and cannot work properly in an acidic environment.

Barrier Damage

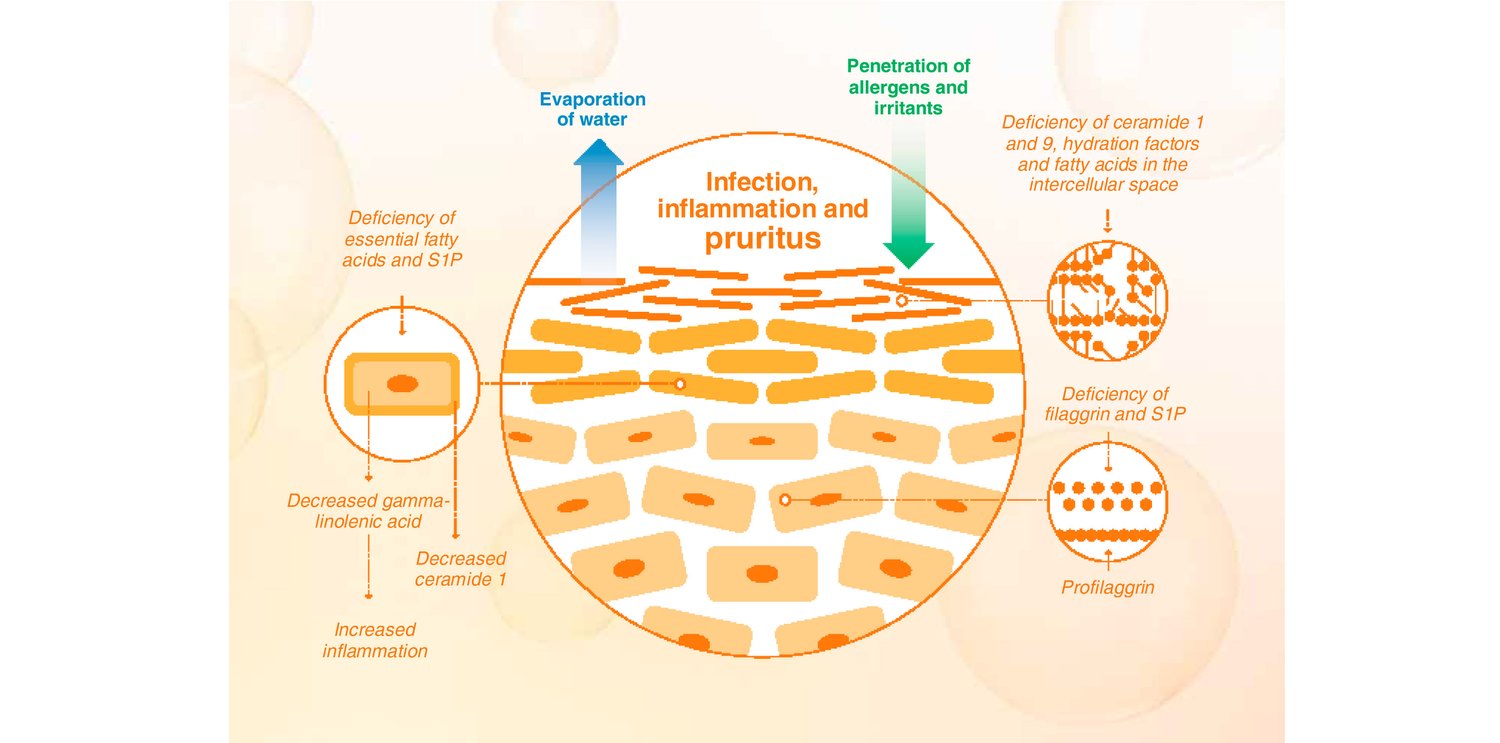

I have discussed the concept of the leaky gut at length in previous blogs and its relationship to eczema. A leaky gut allows foreign materials to pass between intestinal cells and encounter the bloodstream. Our immune cells encounter these unwelcome invaders and mount a massive immune response. To draw a comparison, the skin barrier in eczema actually becomes leaky. Normally the skin cells and the multitude of skin proteins, including ceramide and filaggrin, create a watertight barrier to carefully control what may enter our bodies. Specialized white blood cells are able to reach specialized arms through the tight barrier (without affecting the integrity) and feel the bacteria to determine if they are friend or foe. In eczema, these tight junctions are compromised, and bacteria are able to move into our deeper skin layers. The gaps also allow water to escape, further hampering the normal function of the skin.

But a leaky skin barrier alone is not enough to cause eczema – but it adds to the inflammatory bucket. Even in patients with a severe genetic defect in filaggrin, who are not able to maintain a normal barrier, many of them will never develop eczema. Other factors must contribute to the complex process of eczema.

We are just beginning to understand many of the complex interactions between the microorganisms on our skin. But it is clear that these interactions are altered in disease states such as eczema. It also brings to question so many of the products we have used in daily life. The antibacterial soaps, cleansing agents, and numerous chemicals we have wielded to “kill germs” in our houses clearly have an effect on our skin. We have known for years that fastidiously clean households have a higher incidence of atopic diseases like allergic rhinitis, eczema, and asthma – reinforcing the concept that may be the best thing you can do for your kids is let them play in the dirt or on the floor of the New York City subway to build healthy skin biomes before eczema appears.

And so it was with the above information in mind that I made the next move with my patient Tyler. I believe Tyler had a major imbalance in her skin microbiome and so we began attempts to normalize the ratio of good to bad bacteria in her skin. First, we looked at any environmental agents at home that would alter the pH in her skin: detergents, soap, toothpaste, countertop cleaners, sunscreen, bug spray, plug in air fresheners, water and indoor air quality, and dust mite protection. Then, I needed to use an antimicrobial agent on her skin to reduce the amount of staph aureus and allow the good bacteria to repopulate.

There are several options to control a topical infection, and oral antibiotics are not needed in most cases. (Please speak with your doctor if your child has a skin infection for appropriate treatment). For Tyler, since her infection was moderate to severe I put her on a prescription topical antimicrobial protocol while also using a hypochlorous acid formulation to reduce the pH of the skin and further reduce bacteria counts. As her skin healed, I weaned her off the prescription medication, continued the hypochlorous acid and added a skin rebalancing cream. Over 2 months her skin cleared up. This lovely young girl helped me dig deeper into other causes of eczema and develop more comprehensive protocols to address the skin microbiome. It also reminded of the premise of holistic care – treating the whole person, inside and out.

Check out my Eczema Transformation Program – Book A Call To Learn More

In Good Health,

Dr. Ana-Maria Temple

Was this helpful? Save it for later!